Blog

Moral Development | How Humans Learn Ethics and Values

You know what’s wild? Watch any three-year-old at a playground. They’ll snatch a toy right out of another kid’s hands without even blinking. Fast forward ten years, and that same kid might be organizing a fundraiser for homeless shelters. What happened in between? That’s moral development in action, and honestly, it’s one of the coolest things about being human.

What Moral Development Really Means

Moral development is the process through which we learn to understand, internalize, and apply ethical principles throughout our lives. Think of it as your internal compass slowly calibrating itself from childhood through adulthood. It’s not about memorizing a list of rules—it’s about developing the ability to think critically about ethical dilemmas and make decisions that align with your values.

This process doesn’t happen overnight. Just like you wouldn’t expect a six-year-old to drive a car, we can’t expect young children to grasp complex ethical concepts. Moral development unfolds in stages, with each phase building on the previous one. What’s truly remarkable is that this journey looks surprisingly similar across different cultures, even though the specific values might differ.

The Foundation: Piaget’s Early Insights

Before we dive into the main theories, we need to talk about Jean Piaget. This Swiss psychologist wasn’t specifically studying moral development—he was fascinated by how children think. But his observations laid the groundwork for everything that came after.

Piaget noticed something interesting while watching children play marbles. Younger kids treated the rules as sacred and unchangeable, handed down from some higher authority. They couldn’t imagine that rules could be different or modified. Older children, however, understood that rules were social agreements that people created and could change through consensus. This observation led Piaget to identify two main stages: heteronomous morality (where morality comes from outside authority) and autonomous morality (where individuals develop their own moral reasoning). Kids in the first stage judge actions by their consequences—breaking five plates accidentally is worse than breaking one on purpose. Children in the autonomous stage consider intentions—they understand that accidents differ from deliberate actions.

Where It All Started: Piaget’s Game-Changing Observations

Back in the early 1900s, this Swiss guy named Jean Piaget was watching kids play marbles. Sounds boring, I know. But he noticed something fascinating. The little kids? They treated the rules like they were carved in stone tablets. “That’s just how you play marbles. End of story.” The older kids though? They’d argue about rules, change them, make up new ones. They got that rules were just… made up by people. Mind-blowing for a six-year-old, apparently. Piaget saw two big phases. First, kids think morality comes from outside—from parents, teachers, God, whoever’s in charge. They judge things by what happened, not why it happened. Break five plates by accident? You’re in bigger trouble than if you broke one on purpose. Makes no sense to us, but that’s genuinely how young kids think. Later, they start developing their own moral compass. They understand intentions matter. They realize that sometimes breaking a rule might actually be the right thing to do. That’s when things get interesting.

Kohlberg’s Theory: The One Everyone Talks About

Lawrence Kohlberg took Piaget’s work and absolutely ran with it. In the 1950s, he started asking people—kids, teenagers, adults—about moral dilemmas. Not easy ones either.

His famous example goes like this: There’s a guy named Heinz. His wife’s dying from cancer. There’s a cure, but the pharmacist is charging crazy money—like ten times what it costs to make. Heinz tries everything. He begs, borrows, sells whatever he can. Still not enough. So the question is: Should Heinz break into the pharmacy and steal the drug? Now here’s Kohlberg’s genius move. He didn’t give a damn whether you said yes or no. He wanted to know WHY you thought that. Your reasoning—that’s what mattered. Revolutionary stuff for psychology back then.

Breaking Down How We Actually Think About Right and Wrong

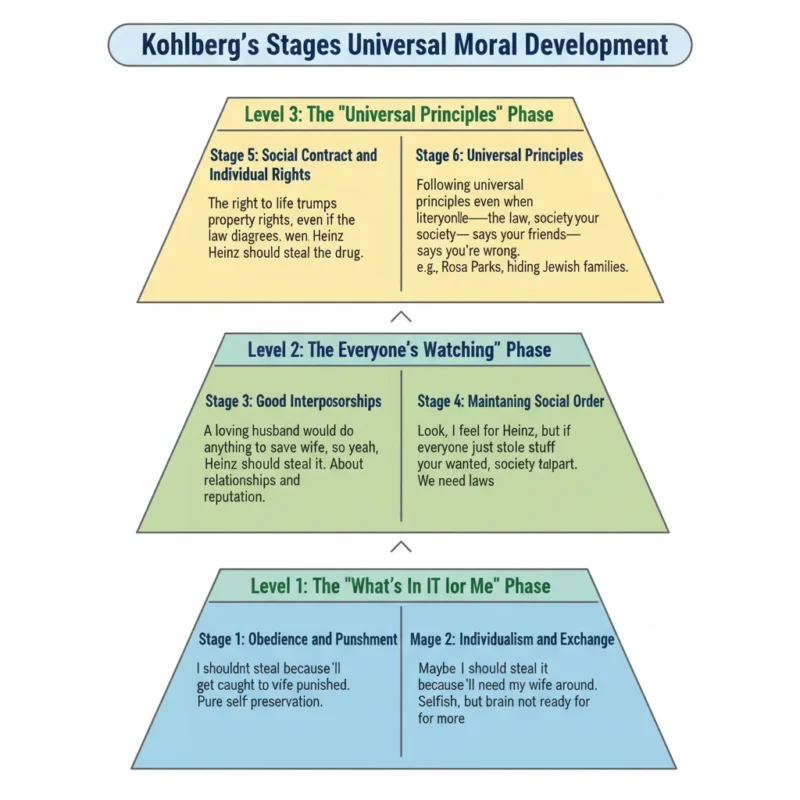

Kohlberg laid out six stages in three levels. Let me break them down without putting you to sleep.

The Problem Everyone Ignored Until Gilligan Showed Up

Carol Gilligan worked with Kohlberg for a while. Then she noticed something he’d completely missed: he’d basically only studied boys and men. Oops.

When Gilligan studied how girls and women approached moral stuff, she found a different pattern. Kohlberg’s theory was all about justice, rights, principles—pretty masculine concerns, if we’re being honest. Women often focused more on relationships, care, not hurting people.

Take that Heinz dilemma. Guys might debate abstract principles about property versus life. Women were more likely to ask practical questions: “Has Heinz talked to the pharmacist’s family? Could the community help? Are there payment plans?” Different approach entirely.

Gilligan wasn’t saying one way is better. She was saying maybe we’ve been measuring everyone with a ruler designed for only half the population. Her “ethics of care” showed that there’s more than one path to sophisticated moral thinking.

What Actually Shapes How We Learn Right From Wrong

Okay, so theories are great and all, but what really matters? What actually influences how kids develop their sense of right and wrong?

Family comes first, obviously. You don’t learn morals from a textbook. You learn them at the dinner table when your parents talk about their day. You learn them when you see how they treat the waiter at a restaurant. You learn them from what they get mad about and what they let slide.

Studies show that parents who are warm but firm—not dictators, not pushovers—raise kids with stronger moral development. Makes sense. Kids need to feel safe to ask questions, but they also need boundaries to push against.

Culture sets the stage. What counts as “right” in one place might be totally wrong somewhere else. Some cultures put the individual first. Others say family or community comes before everything. These cultural values directly influence our lifestyle choices, from how we treat strangers to how we make daily ethical decisions. Neither is more “evolved”—they’re just different value systems.

Friends matter more than we want to admit. Especially for teenagers. Your kid might listen to you about some things, but their friends? That’s who’s really influencing their moral lifestyle and daily choices. This can go either way. Good friends can push each other toward better behavior. Bad influences… well, you know how that goes.

Life experiences expand your world. College students often show faster moral development, not because they’re taking ethics classes (though that helps), but because they’re meeting people totally different from them. Travel does this too. Reading does this. Anything that makes you go “huh, I never thought about it that way” pushes your moral thinking forward.

Why This Stuff Matters in Real Life

You might be thinking, “Okay cool, but why should I care about theories from decades ago?” Fair question.

If you’re a parent, this framework is a lifesaver. Your five-year-old isn’t being manipulative when she only cares about not getting in trouble—that’s literally where her brain is developmentally. Your teenager isn’t weak because he cares so much what his friends think—he’s right on track. Knowing this keeps you from freaking out and helps you guide them appropriately for their stage.

If you’re a teacher, you can’t teach five-year-olds about systemic injustice and expect it to stick. But you CAN help them practice taking turns and thinking about how their actions affect others. High schoolers? They’re ready for real ethical debates about society, justice, all that heavy stuff.

For everyone else, understanding these stages helps you get why people disagree so intensely about moral issues. Your uncle who’s all about law and order? He’s thinking at stage four. Your activist friend who wants to overturn unjust systems? Stage five thinking. They’re literally operating from different frameworks. Neither is stupid—they’re just thinking differently. This understanding shapes how we live our lives, influencing our lifestyle decisions, relationships, and the values we choose to prioritize every day.

The Gaps We Need to Talk About

No theory is perfect, and Kohlberg’s definitely has holes. For one, it might just reflect Western values more than universal human development. He was an American studying mostly Americans. That matters.

Also, his whole focus on reasoning ignores emotions, and anyone who’s made a tough moral decision knows feelings play a huge role. You don’t coldly calculate whether to help someone in danger—you feel it in your gut.

And the staged approach? Maybe too rigid. People don’t think consistently across all moral issues. You might reason at stage five about environmental issues but stage three about family loyalty.

Recent brain research has added new layers. Turns out moral judgment lights up both reasoning and emotional centers in the brain. It’s not just thinking—it’s feeling, social pressure, even biological drives all mixed together.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Understanding moral development isn’t about judging people who think differently than you do. It’s about appreciating the journey we’ve all taken from “don’t hit because you’ll get timeout” to (hopefully) actually caring about making the world better.

The beautiful thing? We never stop developing. You can always deepen your ethical thinking, question your assumptions, grow. Whether you’re raising kids, teaching, or just trying to be a decent human in a complicated world, understanding how moral development works makes you a bit more patient, a bit more thoughtful.

The real question isn’t “what stage am I at?” It’s “am I still growing? Still questioning? Still willing to examine what I believe and why?” That’s what matters.

References

- Kohlberg, L. (1981). The Philosophy of Moral Development: Moral Stages and the Idea of Justice. Harper & Row.

- Piaget, J. (1932). The Moral Judgment of the Child. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Harvard University Press.

- Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. Praeger Publishers.

- Turiel, E. (2002). The Culture of Morality: Social Development, Context, and Conflict. Cambridge University Press.