Blog

Tibia and Fibula: The Complete Anatomy of Your Leg Bones

Ever looked down at your legs and wondered what’s actually going on beneath the skin? Most of us take our legs for granted until something goes wrong.

The tibia and fibula are the two bones that make up your lower leg. They do a lot more heavy lifting (literally) than most people realize.

Whether you’re a nursing student, a curious athlete, or someone recovering from a leg injury, this guide breaks down everything about these two essential bones their structure, differences, how they work together, and why they matter to your everyday movement.

What Exactly Are the Tibia and Fibula

The tibia and fibula are two long bones located between your knee and ankle. Both are classified as long bones and belong to the appendicular skeleton.

They sit side by side but serve very different purposes:

- The tibia is the larger, stronger bone on the inner (medial) side of the leg.

- The fibula is the thinner, more delicate bone on the outer (lateral) side.

A Handy Memory Trick:

Mixing them up? Use this mnemonic: “Never tell a little fib.”

The fibula is the smaller bone “little fib.” And the “L” in “little” reminds you the fibula sits on the lateral side. Thousands of students swear by this trick.

The Tibia: Your Leg Main Load Bearer

Why the Tibia Is Called the “Shinbone”:

Ever bumped your shin on a coffee table? That’s the tibia. The word “tibia” comes straight from Latin and literally means “shinbone.”

It’s the second-largest bone in your body, right after the femur. Because very little muscle or fat covers its front surface, it’s easy to feel — and painfully easy to bruise.

The Upper End (Proximal Tibia):

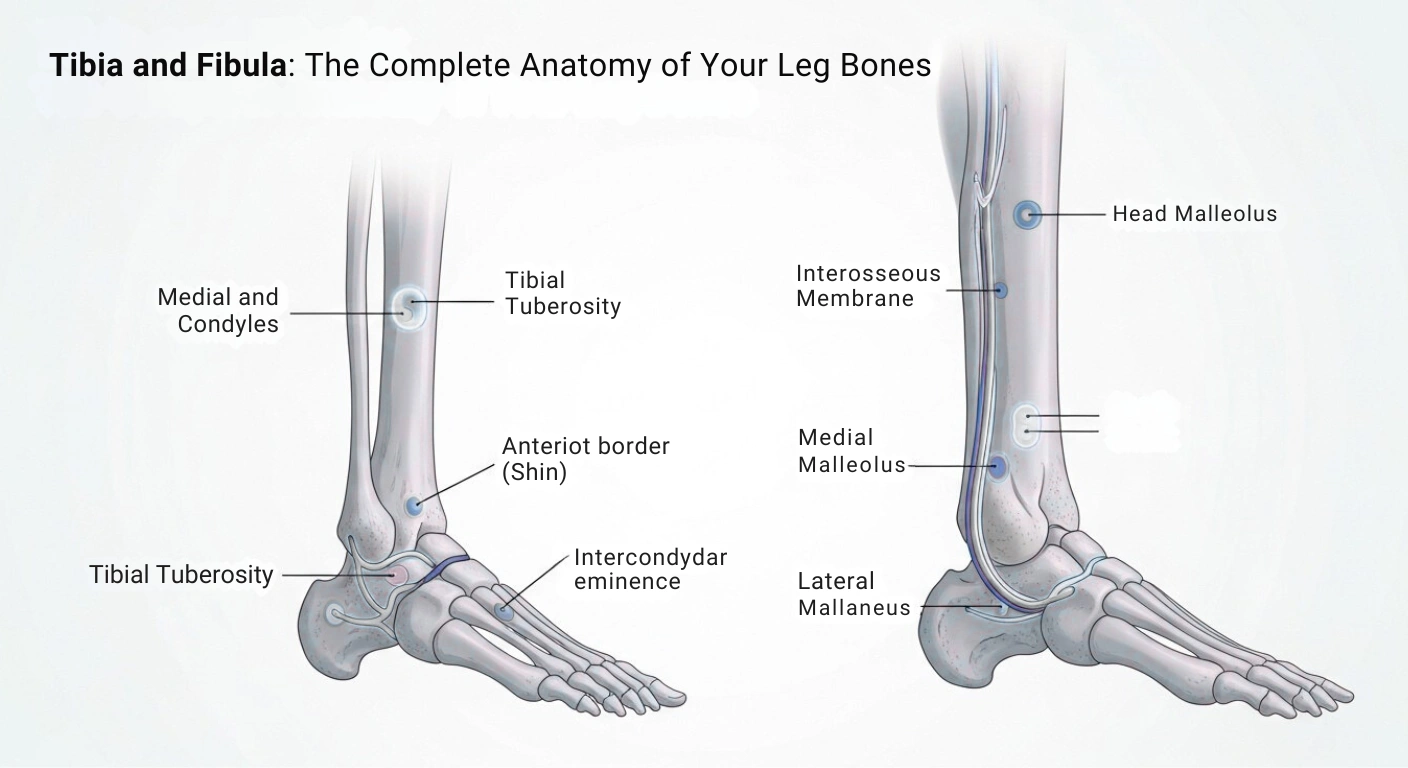

The top of the tibia is wide and flat, forming the tibial plateau. This plateau has two smooth surfaces called the medial and lateral condyles.

Key structures at the proximal tibia include:

- Medial and lateral condyles — rounded projections that articulate with the femur to form the knee joint (tibiofemoral joint).

- Intercondylar eminence — a raised area between the condyles featuring two small tubercles where cruciate ligaments and menisci attach.

- Tibial tuberosity — a bony bump on the front surface where the patellar ligament connects your kneecap to your shinbone.

The Shaft (Diaphysis) of the Tibia:

The middle section has a distinctive triangular cross-section with three borders:

- Anterior border (anterior crest) — the sharp ridge you feel along your shin where deep fascia attaches.

- Medial border — runs along the inner side.

- Interosseous border — faces the fibula and anchors the interosseous membrane.

The anterior crest is subcutaneous — right under the skin with zero muscle padding. That’s why shin injuries hurt so badly. There’s nothing between the outside world and the bone’s nerve-rich periosteum.

The Lower End (Distal Tibia):

At the bottom, the tibia widens again and forms part of the ankle joint. Important landmarks here include:

- Medial malleolus — the bony bump on the inside of your ankle. Fun fact: “malleolus” comes from Latin meaning “little hammer.”

- Fibular notch — a depression on the lateral side where the fibula attaches, forming the distal tibiofibular joint.

- Inferior articular surface — sits on top of the talus bone, creating the main weight-bearing surface of the ankle.

The Tibia as a Clinical Landmark:

Here’s something most people don’t know: the area just behind the medial malleolus healthcare providers check for the posterior tibial pulse. It’s a standard pulse point used to assess blood flow to the foot making the tibia both a structural bone and a clinical roadmap.

The Fibula: The Unsung Hero of Your Lower Leg

Don’t Underestimate the Smaller Bone:

Many people assume the fibula is unimportant because it doesn’t bear much weight. That’s a mistake.

The fibula carries about 10–17% of your body’s load, but it serves as a critical attachment site for muscles and ligaments. Without it, your ankle would be dangerously unstable. It’s also the third longest bone in your body.

The Upper End (Proximal Fibula):

The top of the fibula is called the head and has a wedge-shaped appearance. Key details:

- It articulates with the lateral condyle of the tibia at the proximal tibiofibular joint.

- It provides attachment for the biceps femoris (a hamstring muscle) and the fibularis longus.

- The common peroneal nerve wraps around the fibular neck just below the head.

That nerve matters clinically. Injuries here can cause foot drop — a condition where you can’t lift the front of your foot. Ever sat awkwardly and your foot went numb? That nerve was likely getting compressed.

The Shaft of the Fibula:

The fibular shaft is thin with four surfaces, making it a prime attachment point for lower leg muscles, including:

- Peroneus longus and brevis

- Extensor digitorum longus

- Soleus

- Flexor hallucis longus

How the Tibia and Fibula Connect to Each

These two bones aren’t floating independently. They connect at three key points:

- Proximal tibiofibular joint — at the top, allowing minor gliding movements.

- Interosseous membrane — a tough sheet of connective tissue running the length of both bones.

- Distal tibiofibular joint (syndesmosis) — at the bottom, holding the bones tightly to form a stable ankle socket.

What Does the Interosseous?

Break down the word: “inter” means “between” and “osseous” means “bone.” It’s literally the membrane between the bones.

This membrane does several important jobs:

- Holds the tibia and fibula together while allowing slight movement.

- Separates the anterior and posterior muscle compartments of the leg.

- Distributes forces between both bones during movement.

- Serves as an attachment site for several leg muscles.

Interestingly, the radius and ulna in your forearm have a very similar interosseous membrane it’s a design the body loves to reuse.

Blood Supply and Nerve Innervation

How Blood Reaches These Bones:

Each bone has its own blood supply:

- Tibia — receives blood primarily from the nutrient artery (a branch of the posterior tibial artery), entering through the nutrient foramen on the posterior shaft. The periosteum also provides blood through periosteal arteries.

- Fibula — supplied by a nutrient artery from the peroneal (fibular) artery. The proximal head also receives branches from the anterior tibial artery.

Understanding fibular blood supply is especially important for surgical planning when the bone is used for grafting.

Nerves Around the Lower Leg:

Two major nerves pass close to these bones:

- Tibial nerve — runs along the back of the leg, supplying posterior compartment muscles.

- Common peroneal nerve — wraps around the fibular neck, then splits into deep and superficial peroneal nerves supplying the anterior and lateral compartments.

Common Injuries and Conditions

Tibial Shaft Fractures:

The tibia is the most commonly fractured long bone in the body. Its subcutaneous position makes it vulnerable to direct impact from car accidents, sports collisions, and falls. Severe cases can involve open fractures where bone breaks through the skin, carrying high infection risk.

Stress Fractures and Shin Splints:

These are the bane of runners and military recruits:

- Stress fractures — tiny cracks from repetitive loading over time.

- Shin splints (medial tibial stress syndrome) — pain along the inner edge of the tibia from overuse or sudden increases in activity.

Fibula Fractures and the Danis-Weber Classification:

Fibula fractures often occur with ankle injuries. Doctors classify lateral malleolus fractures using the Danis-Weber system:

- Type A — fracture below the syndesmosis.

- Type B — fracture at the level of the syndesmosis.

- Type C — fracture above the syndesmosis.

This classification guides treatment decisions. Avulsion fractures where bone gets pulled away by attached muscle or ligament can also affect the fibula.

High Ankle Sprains:

Injuries to the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis are called high ankle sprains. They’re more severe than typical lateral sprains, with longer recovery times. Contact sport athletes in football, hockey, and rugby face the highest risk.

Compartment Syndrome:

In rare but serious cases, fractures involving both bones can cause compartment syndrome dangerous pressure buildup within the leg’s tight muscle compartments. This restricts blood flow and can cause permanent damage if not treated with emergency surgery.

The Role of the Tibia and Fibula in Movement

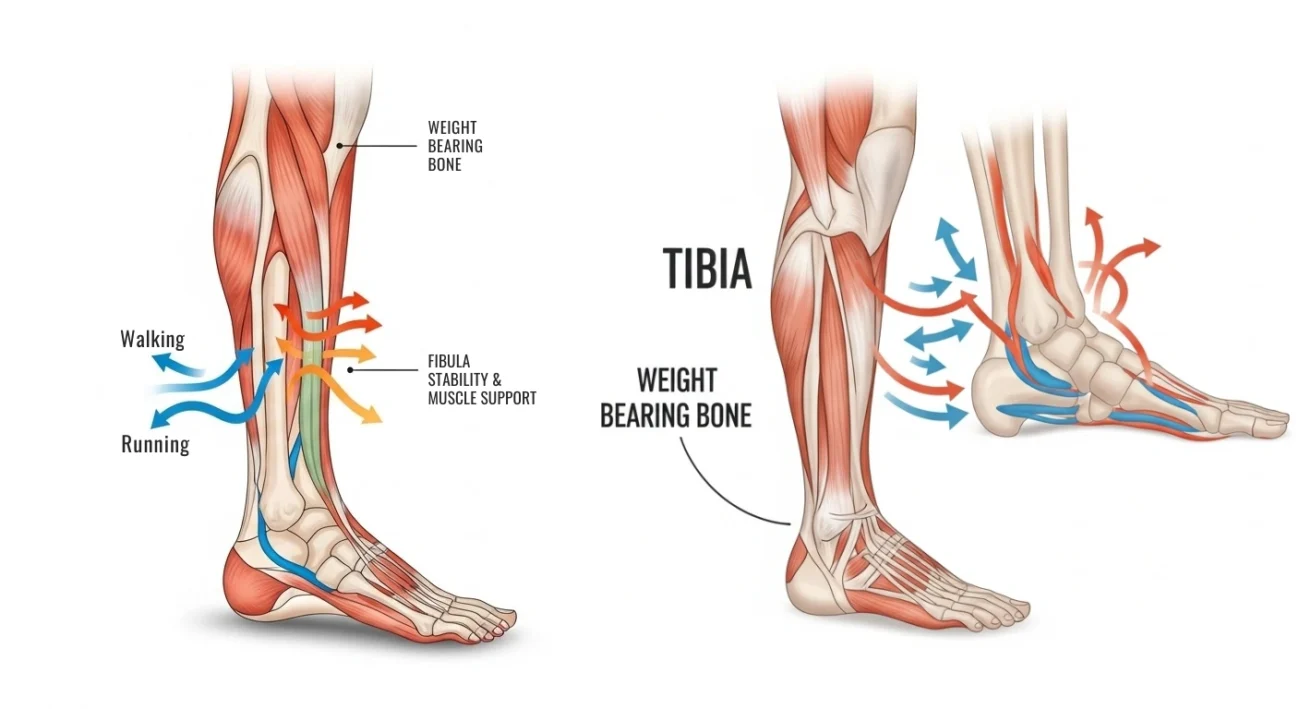

Walking and Running Mechanics:

Every step you take, the tibia absorbs and transmits forces from your body weight and the ground’s reaction. The fibula stabilizes the ankle’s lateral side and provides leverage for muscles controlling foot position. The interosseous membrane distributes forces between both bones during dynamic activities.

Muscle Attachments That Drive Motion:

The lower leg has four muscle compartments, and the tibia and fibula serve as the framework for all of them:

- Anterior compartment — tibialis anterior (lifts your foot).

- Lateral compartment — peroneals (stabilize your ankle).

- Superficial posterior — gastrocnemius and soleus (push you off the ground).

- Deep posterior — tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus (support the arch and flex toes).

Development and Growth of the Tibia and Fibula

How These Bones Form:

Both bones develop through endochondral ossification a process where a cartilage model is gradually replaced by bone tissue. This starts around the 7th to 8th week of fetal life.

Key ossification timeline for the fibula:

- Lower epiphysis ossifies around year 2.

- Upper epiphysis ossifies around year 4.

- Lower epiphysis fuses with shaft around age 20.

- Upper epiphysis fuses around age 25.

Growth Plates and Their Importance:

In children and teens, the growth plates (epiphyseal plates) at each end of these bones are responsible for lengthwise bone growth. These cartilage plates are fragile compared to mature bone.

Damage to a growth plate can disrupt normal bone development and lead to limb length differences which is why pediatric fractures near the ends of these bones require careful monitoring.

The Fibula in Reconstructive Surgery

Here’s something most anatomy resources skip: the fibula is the gold standard bone graft for rebuilding the jawbone (mandible).

Why the fibula? Several reasons:

- It doesn’t bear significant body weight, so removing part of it doesn’t ruin your ability to walk.

- Its long, thin shape is perfect for reshaping into a jaw.

- It has excellent blood supply for tissue integration.

During fibular free flap surgery, surgeons harvest the middle third of the fibula along with its blood vessels (and sometimes surrounding skin and muscle). They reshape it and transplant it into the jaw.

Final Thoughts

At the end of the day, the tibia and fibula are the unsung heroes holding you up with every step, every run, and every jump. The tibia does the heavy lifting while the fibula quietly keeps your ankle stable and your muscles anchored. Understanding these two bones gives you a deeper appreciation for the remarkable engineering hiding beneath your skin and next time you bump that coffee table, you’ll know exactly which bone to blame.